In my teens, I would sometimes be in situations where boys pressed to go further than I wanted. I learned how to steer busy hands back up north and to try to make it all as nicey-nice as possible so they didn’t feel wounded and I didn’t feel threatened. Some times were more successful than others.

My struggles with boys and then men were a metaphor for my general struggle with boundaries, self-care and being myself. I didn’t even know these terms or that they were an option for me. Everything revolved around pleasing others to gain attention, affection, approval, love and validation, or avoiding conflict, criticism, rejection, disappointment and loss. I suppressed and repressed my needs, expectations, desires, feelings and opinions because I’d learned to believe that they didn’t count.

It took grappling with a life-threatening illness in my late twenties to finally prioritise my discomfort over other people’s pleasure and satisfaction that came at my expense.

That’s when I heard the term boundaries for the first time. Terrified as I was at the thought of taking ownership of my happiness and well-being and saying no when I needed, should or wanted to, dying scared me more.

So, bit by bit, day by day, I finally started taking care of myself by paying attention to me. I’d believed that this would lead to abandonment, conflict and criticism. Instead, my relationships, self-esteem and health flourished. Eight months later, I was in remission from my “incurable” disease and embarking on a new relationship with my now-husband.

Almost fifteen years on from the day I took my first step to freedom by saying no even though I was expected to say yes, the pandemic has reminded me how it often takes something life-threatening to give us the permission to do what we’ve always had the option of doing.

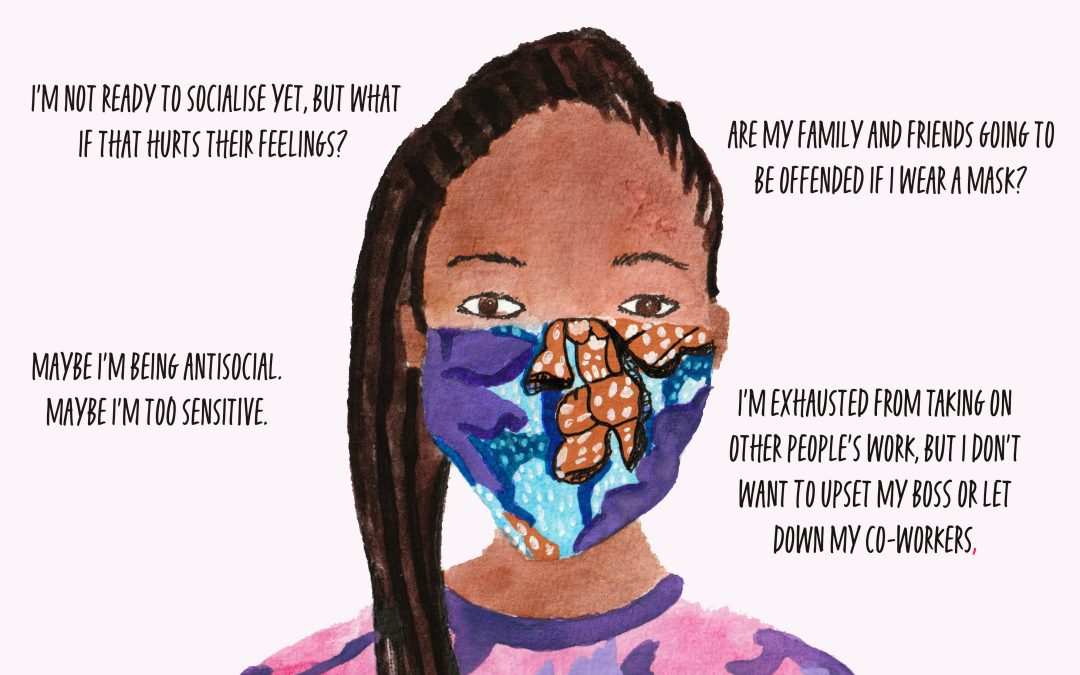

Do any of these concerns and issues sound familiar?

- What if they feel offended that I wore a mask or that I prefer to social distance?

- [What they’re asking of me] is way too much, but I can’t say no. My boss/colleagues need me. If I have to do the work of ten people and ignore my health or my family, so be it.

- I’m not ready to socialise yet, but I feel like I have to because family/friends are. I don’t want to be the odd one out or have them thinking/talking negatively of me.

- We’ve been dating for X weeks/months, but we’re not in a relationship. I want to ask if they’re seeing other people, especially with COVID-19 and the need to be careful, but I don’t want to be seen as needy/demanding/impatient.

- They’ve been going in and out of people’s homes throughout lockdown and not following social-distancing guidelines. Now they want to hang out, and I don’t want to, but I don’t want to seem fussy or judgmental.

- This virus is bullshit and I refuse to wear a mask. Why can’t people keep their discomfort about this to themselves?

Prior to the pandemic, plenty of us would have sworn up and down that we don’t have a problem with boundaries or that we’re not a people pleaser. Even though in the same breath, we might have admitted that we routinely take on too much, sometimes pretend to be something we’re not, struggle to prioritise ourselves or keep running into the same conflicts, we didn’t see it as a boundary issue. We may not have associated our habits with people pleasing. Even if we did, we thought we were being helpful, loving, empathetic or asserting our needs.

The pandemic throws a spotlight on society’s general problem with boundaries. So many of us have been socialised to believe that factoring our needs into our actions, thoughts and choices is “selfish”, not a fundamental component of healthily functioning as a human being within our interpersonal relationships.

We’ve been taught that boundaries hurt feelings and inconvenience and alienate others. That they’re not something you do or have when you love someone or you want to keep getting a paycheque. On the flip side, though, we’ve also picked up the confusing message that saying we don’t like or want to do something is a boundary that we can impose upon others.

Thanks to the pandemic, we can stop kidding ourselves that we have great boundaries. People pleasers can stop pretending that life isn’t one big anxiety see-saw caused by near-constantly trying to cater to other people’s feelings and opinions as a way to feel good about ourselves.

The pandemic is a situation where we’re dealing with an invisible threat. We have mixed protocols, mixed responses, mixed boundaries, mixed everything. Different places and people are doing different things. Some of the higher-uppers managing the response couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery and flout the rules to suit themselves.

Sure, there’s a possibility if we get Coronavirus that we’ll be asymptomatic or that we’ll recover with little or no long-lasting effects. There’s also, however, a distinct possibility it will go the other way. Even if we don’t die, we could be left with life-long effects. And this is before we consider that this flipping thing is highly transmissible and so our actions, including our hygiene and distancing boundaries, even if they don’t appear to impact us, have the potential to impact others. That’s boundaries 101.

Boundaries are the often invisible lines between us and others.

We might not be able to see them or know how they personally manifest with each individual, but they’re there. Cross ours or others, and our body, the dynamic or the situation will communicate it.

We all have emotional, mental, physical, spiritual and what I call stuff-of-life boundaries (attitude to giving, receiving, borrowing, material goods, etc). Each person’s boundaries are personal. What feels good and right for me along with what doesn’t, is different for someone else.

While discomfort alerts us to potential or actual boundary issues, boundaries are also about how we honour our needs and values so that we can welcome more of the things we want to be, do and have. This means that boundaries require us to know the difference between us and others. We have to respect our boundaries (and those of others) even though we are sometimes going to be around people whose boundaries radically differ from ours.

So, let’s revisit those concerns and issues:

What if they feel offended that I wore a mask or that I prefer to social distance?

The mask and social distancing reflect your values and how you want to take care of your health. You wearing a mask or social distancing to protect yourself from Coronavirus doesn’t infringe on someone’s needs or well-being. It’s not a criticism of someone else’s choice. No one needs you to endanger your life unnecessarily. Our attitude about protection during the pandemic has stark parallels with some people’s attitudes to using protection during sex. Your body, your health, your choice.

[What they’re asking of me] is way too much, but I can’t say no. My boss/colleague(s) need me. If I have to do the work of ten people and ignore my health or my family, so be it.

I get wanting to protect your job and be a ‘good employee’ and sometimes going above and beyond. You don’t have unlimited bandwidth though. Not communicating your bandwidth and limits is a boundary issue that puts you at risk of burnout. It might also cut your salary by half (or more) depending on how many hours or jobs you’re doing. Why are you making you solely responsible for other people’s problems? Why are you sheltering your boss/colleagues from the reality that something is being mismanaged? You overworking and being over-responsible won’t fix this; it will reinforce the problem. Also, people can’t know what your bandwidth is if you don’t communicate it. You have a right to a personal life.

I’m not ready to socialise yet, but I feel like I have to because family/friends are. I don’t want to be the odd one out or have them thinking/talking negatively of me.

Trying to control other people’s feelings and opinions is like trying to cup the ocean in your hands. If you’re going to socialise, do so because you want to, not because you feel pressured or because you emotionally blackmailed you into it. These are not loving reasons to spend time around loved ones! Will not going feel uncomfortable? Absolutely. But what’s the alternative? Force you to do it by telling you that you’re ‘antisocial’ or ‘too sensitive’ and then be riddled with anxiety, resentment and self-hate? Your discomfort is your discomfort. Own it and create boundaries that reflect it.

Going back to the parallels between the pandemic and sex: sex because you want to feels different to doing it when you’ve been coerced or shamed into it. You’re on different timelines and possibly have different values. You don’t need to judge them or you; judge the situation. Yes, they might be disappointed. This is OK. All humans need to experience disappointment so that they create healthier expectations and boundaries.

We’ve been dating for X weeks/months, but we’re not in a relationship. I want to ask if they’re seeing other people, especially with COVID-19 and the need to be careful, but I don’t want to be seen as needy/demanding/impatient.

Reticence about defining the relationship is an age-old issue, but the pandemic is a call to stop being ambiguous about your needs and values. Asking if your partner’s dating other people might involve hearing something that you don’t want to hear, but it’s still something you need to know. You might be mixing with more people than you realised!

Calling yourself needy/demanding/impatient or whatever is a sign that you’re crossing your boundaries. Where else does this manifest in your dating and relationship experiences? If you can’t ask questions or be honest about who you are and what you need, you don’t have a relationship, pandemic or not. There’s a part of you that might argue that some crumbs and company is better than none, but at what price a relationship or sex?

They’ve been going in and out of people’s homes throughout lockdown and not following social-distancing guidelines. Now they want to hang out, and I don’t want to, but I don’t want to seem fussy or judgmental.

Recognising and acknowledging other people’s values and boundaries is no bad thing. It lets you know where you stand so that you can make emotionally responsible decisions. In turn, you can create boundaries that reflect who you are, how you want to feel, and where you’re headed. If you’ve followed the guidelines and they haven’t, it reflects a difference in values.

If they feel uncomfortable about you not wanting to hang out, that’s OK. Boundaries don’t hurt feelings. They don’t! If there’s upset and discomfort over boundaries, the problem is the nature of your relationship, not your boundaries. What you need to get honest about is why considering yourself is fussy, judgmental or {insert insult of choice}? It’s not about judging them; you need to judge the situation.

This virus is bullshit and I refuse to wear a mask. I don’t like how it feels and I just think it’s silly. Why can’t people keep their discomfort about this to themselves?

What we dislike in others points back to where we are guilty of the same thing. Aren’t you expressing your discomfort with masks and other people’s attitudes in your own way? I appreciate that wearing a mask isn’t something that everyone feels comfortable with*. In situations where what you’re doing doesn’t pose a risk to others, focusing purely on your pleasure, comfort or convenience isn’t an issue. When prioritising these, though, crosses someone else’s physical boundaries, that’s where the issue arises.

Going back to the parallels with our attitudes about safe sex and even pregnancy: pleasure and convenience don’t outweigh impact. Yes, we might prefer bareback to condoms, but that only takes precedence when we’re having sex with ourselves (!!!), the consequences only affect us, or the other party is in mutual agreement. If anything we’re doing as humans involves coercing or shaming others, denying our responsibility, or, yes, endangering someone’s life, then that’s not boundaries.

All that said, how you feel about wearing a mask is your feelings, your beliefs, your values. Yes, in situations where there’s more than you to think of, your stance may flag concern or pose a potential issue, but no one has the right to jump all over your case for your position. Empathy is our ability to consider someone else’s position even though it may differ to ours and we don’t agree with it.

Think of boundaries like this:

In your home, you take your shoes off. You have various reasons. As it’s your home, you get to exercise your preference. If I come to your house, I can’t just decide that I’m going to wear my shoes, whether they’re filthy or ‘clean’ because that’s what I prefer or it’s what I do in my home. It’s not my flipping house! You can tell me to take off my shoes without shaming me. I also don’t need to shame or coerce you into letting me keep them on. Of course, if I come to your house and march through the place with my shoes even though everyone else is barefoot or in slippers and you don’t say anything, you’re not communicating your boundaries. And yes, I’m also not coming from a boundaried place because I haven’t considered the possible existence of your boundaries.

Our individual responses to the pandemic throw up the question of whether we (or others) are being fair and reasonable. The fact that we ask this of ourselves because of masks, wanting to social distance, invitations, or being burnt out and over-responsible highlights what a thoroughly good job society has done of conditioning so many of us into being people pleasers. But everyone has their limit, even a pleaser.

When you’re doing something that has the potential to endanger your emotional, mental, physical or spiritual well-being, if the benefits of doing it outweigh the negative consequences, knock yourself out.

If not, you have to get temporarily uncomfortable and say or show no when you need, should or want to. Your life may depend on it.

It shouldn’t take a pandemic or any other crisis to make us own boundaries that have always been there, but we humans often need breaking point and dire straits to make much-needed change. Wherever we think we are with boundaries and people pleasing, the pandemic invites us all to be more honest and boundaried. This can only be a good thing.

I share scripts and more thoughts on people pleasing and the pandemic in this piece in the New York Times.

*Some people who can’t wear a mask due to it impairing them due to disability. That’s totally different from the above scenario.

For more help with learning to say no when you need, should, or want to, order my new book, The Joy of Saying No: A Simple Plan to Stop People Pleasing, Reclaim Boundaries, and Say Yes to the Life You Want (HarperCollins/Harper Horizon), out now and available at all booksellers.

Add to favorites

Add to favorites